After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Virtual revolution

The nascent virtual reality market is slowly coming of age, with a new crop of VR production companies helping to define what immersive content looks like today. Andy McDonald finds out more.

While it is still early days for virtual reality, a flurry of recent activity hints at how far this space still has to grow. In the past month alone, Google announced it first standalone Daydream VR headsets, VR technology company Improbable raised US$502 million (€450 million) in a Series B funding round led by SoftBank, and Facebook unveiled a new VR app for communicating with friends, called Facebook Spaces.

Market predictions for the space have also been bullish. IDC predicts that total VR headset device shipments will grow almost tenfold from 10.1 million units in 2016 to 99.4 million units in 2021. Greenlight Insights believes that total virtual reality revenues will reach US$7.2 billion globally by the end of 2017, while CCS Insight claims that the total VR device market – both smartphone VR and dedicated VR – will be worth US$1.5 billion in 2017, rising to US$9.1 billion by 2021.

On the content side of things, some of the more established players in this still young space, like St Albans-based Rewind, are involved in all aspects of VR – from interactive games-engine driven work, to mixed reality, and 360° video. However, there is also an emerging trend of talent passing from the traditional TV world over to VR. The people behind production outfits Parable VR, VR City and Mandt VR are all examples of TV experts turning their hands to immersive content. For the most part, their focus so far has been on narrative-led 360° video.

Digital TV Europe spoke to some of these players to find out how the content they are making is helping to define the VR industry today.

Rewind

While many VR companies operating today are rooted in 360° video, UK-based Rewind takes a more holistic view of the virtual reality market. Rewind founder and CEO Sol Rogers describes a space that ranges from desktop browser-based 360° video, delivered through YouTube and Facebook, at one end of the scale, to game-engine driven, fully interactive and fully immersive VR delivered through high-end devices like the HTC Vive or Oculus Rift at the other.

“We’re one of the few companies globally that fit the full umbrella of content,” says Rogers. “When we start working with clients and brands, we are not selling them [on the idea that], ‘we’ve got a box full of these things, so they’re going to be the answer for everything’. We’re going ‘well what are you trying to get out of this?’”

A look at some of Rewind’s recent projects gives you an indication of the scope its work. It recently produced a cross-platform VR experience for Hollywood movie Ghost in the Shell in partnership with Oculus, Paramount, Dreamworks and US-based VR studio Here Be Dragons. Made in just seven weeks, the experience was available on Rift as a “super interactive”, high-end VR experience; as a semi-interactive experience for Gear VR; and as a 360° video version that lives on Facebook. Describing the work, Rogers says: “It’s not the film, it’s not a trailer, it’s something which gives you a glimpse into the universe and it’s stand-alone.”

“The first thing that we do with a client is we try to work out what they want first and foremost,” says Rogers. “What type of content you want to create and really try and work out what the measure of success is.”

A recent project for Jaguar saw Rewind produce a social VR experience at last year’s LA Auto Show for the launch of its all-electric I-PACE concept car. “They wanted it to be a launch event to communicate to 250 journalists this amazing product in an amazing way,” said Rogers, explaining the choice of high-end, real-time, interactive VR. “The value came from doing it that way.”

While only a relatively small number of people saw the Jaguar VR experience, the journalists who wrote about it gave the project a wider reach. “If they [Jaguar] produced a 360° video, they could have got a lot of users, a lot of people seeing it on Facebook and YouTube. But it actually wouldn’t have been much different from producing just a highly polished 2D film,” says Rogers.

Thinking about the development of the VR industry to date, he claims that companies have already had to take a change of tack. “Brands and agencies were enjoying their free PR push that they got about being the world’s first VR something – ‘insert brand’, ‘insert product’. That all went away last summer. Now it’s more about quality of returns.”

While the number of eyeballs watching a video is still important, Rogers says that the transformative effect of experiencing high-end VR communicates a message in more powerful way than by watching something on TV or via YouTube. “For me 360° video is something as a necessary transition, because it’s fantastic for mobile,” says Rogers. “There are 1.9 billion smartphones in the world, all of them can access 360 video and you don’t have to have a headset to view it.” However, he claims that this is a “pale comparison” to a full VR headset experience.[icitspot id=”705021″ template=”pull-quote”]

“The real-time stuff on the Rift, the Vive, the Playstation VR – game-engine driven, where you have control, where you are part of the world and have interactivity – that’s new and that’s a lot slower for the uptake. But once you’ve tried it, you understand that it’s a different medium, a different art form, which is fundamentally going to change everything,” says Rogers.

“Sadly, it takes a little bit of expensive hardware – headsets and PCs – to get us there, so that route is a lot slower than we expected. But it is the one that will win in the long-run.”

Mandt VR

TV industry veteran Neil Mandt remembers a point roughly three years ago when he felt there was “a real problem going on in the industry”, a sense that the “can-do attitude” of the television sector was starting to disappear. It was this instinct that led Mandt to flip his entire TV production company to focus on VR – a medium that, at the time was still only “on the distant horizon”.

“If you’d asked me a decade ago where my career would go, I would have said, ‘TV: that’s what they’re going to put on my tombstone’,” says Mandt. However, what he perceived as a shift in the industry – where deals were getting harder to close and more work and edits were being demanded for commissioned projects – gave him pause for thought.

“At the time, I didn’t know that this whole problem was because of the cord-cutting. Nobody knew it. It was like being in a recession, but you don’t know until you’re six months into it,” says Mandt. Looking to the early-stage VR market, where the content was “not just bad, it was almost unwatchable,” he decided to be among the first clutch of companies to compete in this space.

Mandt’s roots in TV stretch back to his university days, when winning a College Emmy at 19 landed him a job as an NBC reporter aged 20. His career after that point included producing the OJ Simpson criminal trial for ABC News, producing the Sydney Olympics for NBC and creating what he estimates to be around 3,000 episodes of television though his 2001-established production company, Mandt Bros.

His Mandt Bros. credits include ESPN series Jim Rome is Burning, Syfy Channel series Destination Truth, and Food Network series The Shed. Along the way he has also produced a handful of films – including the 2014 Walt Disney Pictures feature Million Dollar Arm, and most recently the Burt Reynolds movie Dog Years, which played at this year’s Tribeca Film festival.

Leaving TV behind and setting up Mandt VR was no small undertaking. Mandt invested in new cameras, new computers and new editing systems for the post-facility at his existing studios in Hollywood. He also had to learn a new production language for 360° content – covering camera placement, sound design and editing techniques.

“There’s storytelling that exists within 2D media, whether it’s on a mobile phone or a computer, where I can tell your brain, without even sound, exactly what’s happening,” says Mandt. “That storytelling is impossible to tell in VR because you can’t cut like that. You can’t push in and zoom. So there is whole new storytelling that needs to happen.”

After doing a handful of videos, Mandt and his partner Gordon Whitener last year raised US$10 million with plans to up their production rate. “We brought in producers who were from traditional television and started training them and making shows. We did a show with [comedian] Tom Green, we did some travel shows and some sports shows -– a variety of different things. That then led us to contract work for some big brands like the Pittsburgh Steelers and Disney,” says Mandt.

He soon realised that to make money in this space, the key would be to replicate the old TV model by making “volume VR” – something that could be achieved through 360° video. “Everyone has a smartphone in their pocket. There’s two billion of them in the world. So we said ‘alright, what 360° video can we make that we can make inexpensively that works within the limitations of both VR and 360°’?”

What followed was a deal with US podcasting company PodcastOne, which will soon see the launch of a PodcastOne VR platform that will house 1,000 pieces of content. Mandt claims this will represent “the most serialised VR 360° content anywhere”. To achieve this, his team built a custom camera rig at the PodcastOne studios that they could access remotely and developed live stitching capabilities for the content. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” says Mandt. “We call the camera the Medusa because it literally has cables coming out of it all over it.”

Looking ahead, Mandt believes that the VR industry is two to five years away from going mainstream. In two years he predicts VR will be a “cool thing” that people will be aware of, but only those in the know will really use. In five years, he predicts it will be the equivalent of where we are today with the smartphone. “I don’t see anything slowing it down at this point.”

Parable VR

Launched in March this year, London-based Parable VR was born out of the combined television and commercial experience of its founders, and has attracted solid industry backing. The company was set up by Nicholas Minter-Green, the former president of Economist Films, and David Wise, the former director of programmes at The Garden Productions – the company behind shows like 24 Hours in A&E. Channel 4 invested in the business through its Independent Growth Fund. The Economist also backed the firm, as did TV industry veteran and Studio Lambert CEO, Stephen Lambert.

Speaking to Digital TV Europe at Parable’s shared office space in London’s Kings Cross, Wise explains that the decision to form the business came about last January after Minter-Green, while still at The Economist, went on a trip to the West Coast of the US and the main talking point among all the tech companies there was VR – despite a limited pool of compelling VR content.

“We weren’t the first to spot it, but we felt, when we looked what was out there, there was a lot of good content but it was lacking narrative,” says Wise of their thinking at the time. “Our belief, in the worlds that we came from, was that you need narrative and engagement in order to sustain audience interest. There was some of that coming through, but not much. That’s why we decided to do it at that point. We felt like this was the beginning of a genuine new phase – of a new medium and it was an opportunity to get in early and we felt excited enough to be willing to abandon our previous careers and transfer our skills across.”

Between January and the summer of 2016 Wise and Minter-Green worked out a business plan and began seeking investment, holding talks with a range of companies and individuals between October and January 2017. Wise says that ultimately they believed “we’d be in a stronger position with organisations who also create and commission content, and have an understanding of content”.

Parable’s first work was Ocean: Mystery Corals, a 360° tour of the corals of Palau in the Western Pacific that was made for The Economist with brand support from Swiss watch company Blancpain.

The company has also recently worked on a brand-funded project, shot in Bermuda, focused on the America’s Cup yacht race. This produced three immersive ‘mini documentaries’, which Minter-Green says point to “all the things that make this medium really exciting, because it allows privileged access, geographic transformation, some speed and sensation.”

Next up is a broadcaster-funded piece, which Wise describes as “pure computer-generated VR”. Talks are also ongoing with broadcasters and established on-screen talent.

“Every single broadcaster I would want to be working with are either thinking about, or are already, commissioning VR,” says Wise. “It will come down to how audiences engage – do viewers come to it in significant numbers and do the broadcasters find a way to make the content available to people in significant numbers?”

Wise says that commercial and public broadcasters alike see VR as a way to engage viewers, particularly hard-to-reach younger audiences. The commercial broadcasters also know that the advertisers who spend money with them are interested in VR, which is in turn helping to fuel their interest in the medium.

“Having come from TV, it’s been amazing to see in the last 10 years the change in the nature of viewing habits and how fragmented the audience has become,” says Wise. “It’s so hard to keep hold of viewers and find an audience. When you have something that by its very nature has all of your attention, that is unbelievably powerful.”

The level of enthusiasm and openness in the nascent VR space is what’s so exciting about it, says Wise. “Anything is possible; that’s a really invigorating thing to be a part of.” He says that Parable’s aim is to create partnerships and help companies to achieve compelling results. “We want to make commercially successful content, which engages a wide audience and which proves that this can have a life beyond isolated bits of content.”

“The question about how sustainable it is as an entertainment medium will come down to the backing it gets and the content that’s created,” says Wise. “You have to trust that the tech companies know what they’re doing. They haven’t done all of this just for fun – they’ve done it because they believe in it as well.”

VR City

VR City started life in 2014 after co-founder Ashley Cowan received a call from an old colleague asking if he knew how to make virtual reality films. “Honestly back then I didn’t, I had no idea,” says Cowan. However, two early pieces of VR content that he had experienced had a tremendous impact on him and spurred him to make steps into that space.

“The first thing I watched was a piece of content called Catatonic. It still lives with me to this day,” says Cowan, describing the Here Be Dragons-produced immersive journey through an insane asylum. “It was genuinely terrifying and I was exhilarated by it.” A second project by the same company, called Clouds over Sidra, which was set in a refugee camp in Jordan, had a similarly big impact.

Cowan’s first piece of VR work was for that former colleague and was an immersive health and safety training video for Pearson Education. This would be the starting point for VR City, which has since gone on to do 360° video work for broadcasters like ITV, the BBC and MTV, and brands like Lexus and Lagavulin.

“I thought, as a medium, it’s got legs,” says Cowan. “Even if it doesn’t make it into peoples’ homes, it can be in classrooms and in training and that’s why our relationship with Pearson was important at the beginning and still is to this day.”

Cowan started his career in TV by working on music and live entertainment shows for MTV, Channel 4 and ITV before setting up London-based East City Films with co-founder Darren Emerson. East City was set up to produce youth-focused entertainment content for brands and international broadcasters, while VR City, the pair’s second production endeavour, has taken them down new roads.

“Very quickly I rediscovered the passion that I used to have in creating content,” says Cowan, describing the genesis of VR City. “I found branded content and youth television wasn’t giving me what I wanted anymore. I didn’t feel like I was being challenged or excited, and I enjoyed the idea of being able to be one of the first. I think that was key.

“Setting up my production company [East City Films], we were walking into a 100-year old industry, along with thousands of others. Whereas in VR we were walking into a one year old industry along with tens. So there was a lot to be said on a personal level for that. But also from a business point of view, it seemed to make sense at the time.”

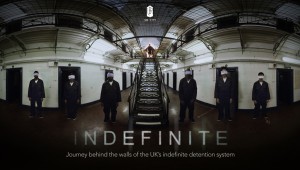

To date VR City has made two immersive documentaries: Witness 360: 7/7, which tells the story of Jacqui Putnam, a survivor of the London 7/7 bombing attacks; and Indefinite, about imprisoned immigrants facing deportation from the UK and the detention system that keeps them locked up.

While the latter was a commission from Sheffield Doc Fest, with a small amount of money also coming from the Arts Council, Cowan says that brands are where its most lucrative work comes from at the moment, “because they can see in the main it’s experiential marketing and there’s reasonably large budgets.”

“That has been our main source of revenue – brands. The slower burn, and very, very interesting to us is to work with people like the BBC, Channel 4, ITV, Sky and BT Sports,” says Cowan. “Everyone’s trying to figure out how it can be funded, because at the moment there is no revenue stream based on people having headsets.”

While Cowan says that there are not yet enough VR headsets in homes, the potential for growth is there to be seen. “The iPhone’s year-one sales were 6.2 million. VR headsets across Oculus, HTC Vive, Google Daydream, Samsung VR are 6.3 million after one year, so it can be spun any number of ways,” he says. “It’s an exciting road to be on, we just need people to continue to invest in it and it will get there.”