After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Is the smartphone TV’s friend or foe?

By next year, 80% of British adults are expected to own a smartphone. Paul Lee, head of research for technology, media and telecommunications at Deloitte, assesses whether phones are likely to erode live TV viewing.

By next year, 80% of British adults are expected to own a smartphone. Paul Lee, head of research for technology, media and telecommunications at Deloitte, assesses whether phones are likely to erode live TV viewing.

For years, most of us had just one screen in our living rooms: the television. Over the past decade, laptops, tablets and smartphones have all muscled in on this relationship.

Of the newer screens, the smartphone has been the most successful: it has had the most commercial impact – it clocked up £250 billion in global sales last year. It has the highest unit sales, with 1.4 billion forecast to be sold this year, of which 1 billion will be purchased as (significantly improved) upgrades.

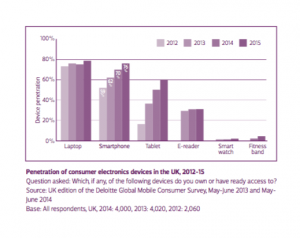

Ten years back, smartphones were expensive, compromised devices, often with more promise than punch. As of May 2015, Deloitte estimates that 76% of UK adults had a smartphone, up six percentage points from last year (see chart, opposite). We expect smartphone penetration to have exceeded 80% of UK adults within a year.

The smartphone market is characterised by a high pace of innovation and a short replacement cycle, with many users upgrading their handsets once every two years.

In the UK, tens of millions of new smartphones are purchased annually; they pack larger screens, faster processors, better connectivity and higher-capacity batteries. The number of transistors (a measure of capability) in the latest high-end smartphones is more than 600 times greater than in a 1995 laptop.

And, overall, smartphones are becoming both better and cheaper: the average selling price for smartphones has declined globally in every recent year, and is forecast to continue to fall until the end of the decade.

Better functionality has stimulated greater usage; lower prices enable greater ownership, and the public has responded. Checking our smartphones instinctively upon waking is a habit common to 11% of smartphone owners; a third of us have looked at our phones within five minutes of rising. A third of 18- to 24-year-olds look at their phones more than 50 times a day.

High penetration and usage rates have catalysed a shifting of creative effort. Games publishers, for example, have an addressable global market of more than 1.5 billion people for their mobile content, but only a few hundred million for console-based games.

The visual sophistication of games created for mobile phones ratchets up each year: compare the first Angry Birds with the high production values in Monument Valley or Leo’s Fortune. Social networks have long since shifted their focus to tapping into mobile usage. Media agencies extol the virtues of mobile advertising, and forecasts suggest that the continued rise of digital advertising spend will be driven primarily by spend on mobile. Mobile dominates the breaking-news market; traditional news formats catch up hours later.

So what does this mean for traditional television? Will the television set surrender its first-screen status to the smartphone? Will content makers shift their creative attention to the five-inch screen, and abandon the 50-inch? Will advertising budgets move to mobile? Or is it the case that television and the smartphone are perfect complements?

Deloitte’s view, based on its latest consumer research, is that smartphones and television largely coexist. They generally address different needs, and are therefore used in different ways.

That said, the smartphone has probably contributed to the decline in television viewing experienced in the UK over the past few years, and may further dent the number of hours of TV we watch. However, what appears very clear is that smartphones have, thus far, not competed head-on with television.

Our assessment, based on research, and also from reviewing other recent studies, is that the primary function of the smartphone is communication: the television’s main role is entertainment, mainly by presenting content with high production values.

We use a widening array of communications tools on our phones. As well as voice calls and text messaging (which are used weekly by nine in 10 adults with a smartphone), we use email (60% of adults), social networks (51%) and instant messaging (46%) to exchange information with others. Aside from voice calls, we are, on the whole, using each communication medium more each year; use of instant messaging, is up 15 percentage points from 2014.

When we reach for our phones first thing in the morning, this is most commonly to check for text messages, email and social networks. We do not, in general, reach for our phones to watch video before getting up.

When it comes to video, the lengthier the content, the lower the degree of usage on a smartphone. Clips are consumed by a large proportion of smartphone owners: 37% of them, or about a quarter of all mobile phone users, watch these when connected to a WiFi network (this falls to 13% when out and about and often reliant on a cellular network).

As for other video formats, about one in seven smartphone owners watches news videos; one in 10 watches catch-up TV; and one in 16 watches live TV or movies.

The latest mobile networks (known as fourth generation, or 4G) have had little impact on video consumption when out and about. Deloitte’s research has found that the majority of recent new subscribers to 4G react to faster network speeds by using communication services more (that is, email, social networks and instant messaging).

While smartphones may not compete with television for watching traditional, long-form video, arguably they could crowd out time and attention that would otherwise have been spent in front of a TV set. After all, more than a third of adults claim to look at their phones more than 25 times a day, and about a sixth look 50 or more times a day. Even the most avid TV viewers would not have two dozen viewing sessions a day.

By contrast, smartphone usage is characterised by brief glances – frequently, checks for updates – whereas television viewing is typified by lengthy gazes. We think mobile addresses different needs to television, and is used at a different time of the day.

Smartphones are our connection to our personal and professional networks, and are used throughout the day, but briefly. For tens of millions, television is an evening activity, used to relax and disconnect, often in the company of others (and smartphones). At present, consumers frequently view television accompanied by their favourite devices.

Our research has found that 22% of adults (and a third of 18- to 24-year-olds) use their phones “very often” or “always” while watching TV. Using a phone would distract from watching a complex drama, but glancing at updates and alerts relayed to a phone can easily be interspersed with watching light entertainment programmes that feature frequent previews and summaries.

We do not think content creators are likely to abandon television in favour of mobile. Some core television genres, including entertainment, drama and sports are formatted for large television screens and can be significantly harder to watch on a small screen. In sports, for example, it may be hard to spot the ball.

One option would be to format content for a small screen; this works readily, and can be automated, for text and even for still images, but is much harder to attain with video. We think it is unlikely that smartphone screens will get much bigger (and therefore able to accommodate these genres), as they will lose their portability. Only a tiny minority of larger-screened tablets are used out of doors.

However, some genres, particularly news and weather, mesh very well with smartphone platforms. Smartphones are well suited to both breaking news alerts and longer feature stories.

After waking, once we have checked for messages, we then tend to turn to news and weather. During the day, about two-fifths of smartphone owners use their devices to read news, with a smaller proportion watching news.

For advertisers, the key advantage that mobile can offer is personalisation; its core limitation is screen size, which diminishes mobile’s ability to show display advertising. We expect the ability to customise advertising will get markedly more sophisticated over time, as new technologies and new data mining techniques come on stream. Future smartphones are likely to become increasingly important for search, including queries prompted by television content.

Arguably, the much greater screen size of TVs, and the ability of television to grab the attention of millions at the same time, mean that it will always be the preferred advertising medium for building brand presence.

In recent years, there has been a focus on developing second-screen apps to accompany television viewing. Our current view is that only a minority of TV viewers “second screen”, such as playing along with contestants on a quiz show. Given the modest take-up so far, this behaviour is not expected to change significantly in the medium term. The less these apps are used, the less investment is likely to go into their creation.

So, as of 2015, we do not think that smartphones have had a sizeable positive or negative impact on the television market; the two have largely co-existed. As mentioned earlier, our view is that the smartphone and television are specialised for different functions, respectively communication and entertainment. There is a caveat, however: the future may not mirror the past.

According to Barb’s measures, hours of live-television viewing in the UK fell by 6% (or 12 minutes), to 193 minutes, in 2014, following a 5% (11 minute) decline in 2013. During these two years, the number of adults with mobile phones increased by about 15 percentage points.

There were multiple factors contributing to this decline, such as gaps in measurement (leading to undercounting of TV consumption) and rising employment (reducing hours available to watch programmes).

However, the rising appeal and usage of smartphones is also likely to have been a factor: nibbling away, for example, at viewing of news bulletins or offering a personalised soap opera via social networks, as opposed to a broadcast one.

Today, television and smartphones are more friends than foes; in the future, influenced by innovations such as virtual reality, their relationship might become adversarial.

This article, written by Paul Lee and based on research from Deloitte, originally featured in the Royal Television Society‘s Television magazine. Read the July/August issue here.