After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

SVODs without advertising are quickly becoming the outlier

Amid all the hullabaloo surrounding Netflix’s recent earnings – from its shocking subscriber loss to the subsequent shareholder lawsuit announced this week – one aspect that went largely underreported was news that the streamer will look to implement an advertising-supported version of the world’s largest SVOD.

The news was somewhat surprising, given comments from the company’s CFO a month prior that it had no plans to implement such an option, but desperate times call for such drastic measures.

Announcing the plan, Netflix’s co-CEO Reed Hastings pointed at a wider industry trend: “It’s pretty clear that it’s working for Hulu, Disney’s doing it, HBO did it. I don’t think we have a lot of doubt that it works. All those companies have figured it out. I’m sure we’ll just get in and figure it out as opposed to test it and maybe do it or not do it. I think we’ll really get in.”

Hastings is right – all the major SVODs from US studios either launched with an advertising-supported option (such as NBCUniversal’s Peacock) or added them not too long after launch (as was the case with Paramount+).

It is this overarching trend which makes a company like AMC appear as a standout. While the media company operates a number of FAST and AVOD channels and platforms, its CEO this week stated that it has no intention on implementing ads to its SVOD services such as AMC+, Acorn TV, Shudder, Sundance Now and UMC.

With what could be construed as a dig at Netflix’s current plight, CEO Matt Blank said: “It’s funny when you hear other large players have some problems in their sub growth, all of a sudden an ad tier is going to solve all problems. We don’t necessarily think that, that’s true.”

Thus the question is raised: does adding a cheaper ad-supported tier actually aid subscriber growth? And more broadly, what are the benefits of adding advertising?

Does adding ads add up to success?

For Matthew Bailey, principal analyst, Media and Entertainment, at research powerhouse Omdia, there are multiple reasons to add advertising beyond purely gaining subscribers.

“There are numerous reasons for this but the main one is profitability,” he says. “Content costs continue to rise, but consumers only have a finite amount of money to spend on OTT subscriptions, especially as cost of living pressures rise.

“The alternative would be for users to churn as they reach the ceiling of their OTT spend – cheaper ad-supported offerings give service providers the chance to retain and continue to monetise their existing subscriber base, as well as attract new types of users that had previously been put off by the higher subscription costs of ad-free services.”

As such it is clearly evident why the major streaming operators are looking to integrate advertising, but Bailey believes that some will fare better than others. He states: “I think that Disney will find it easier to integrate than Netflix. Bear in mind that Disney already has vast experience at operating a hybrid monetisation strategy through its ownership of Hulu.”

The analyst also argues that Netflix’s inexperience of negotiating deals for spot ads “will put it at a disadvantage when looking to take a cut of advertisers’ TV budgets”.

Bailey also points to Disney’s experience with Hulu as the viability of ad-supported streaming, stating that the company “already earns more money from its ad-supported subscribers than it does from its ad-free subscribers.”

Advertising to the Max

Perhaps the closest thing we have to a case study of whether adding advertising to an existing SVOD helps it to grow is HBO Max. (One could argue for Paramount+, but the streamer was less than six months old when ads were implemented, so tracking its growth is more muddled).

Upon its launch in mid-2020, there were a number of key criticisms levied against the WarnerMedia (now Warner Bros. Discovery) streamer. Carriage was one, with the platform not initially supported by Amazon and Roku; while issues surrounding technical performance and confusing branding also were raised.

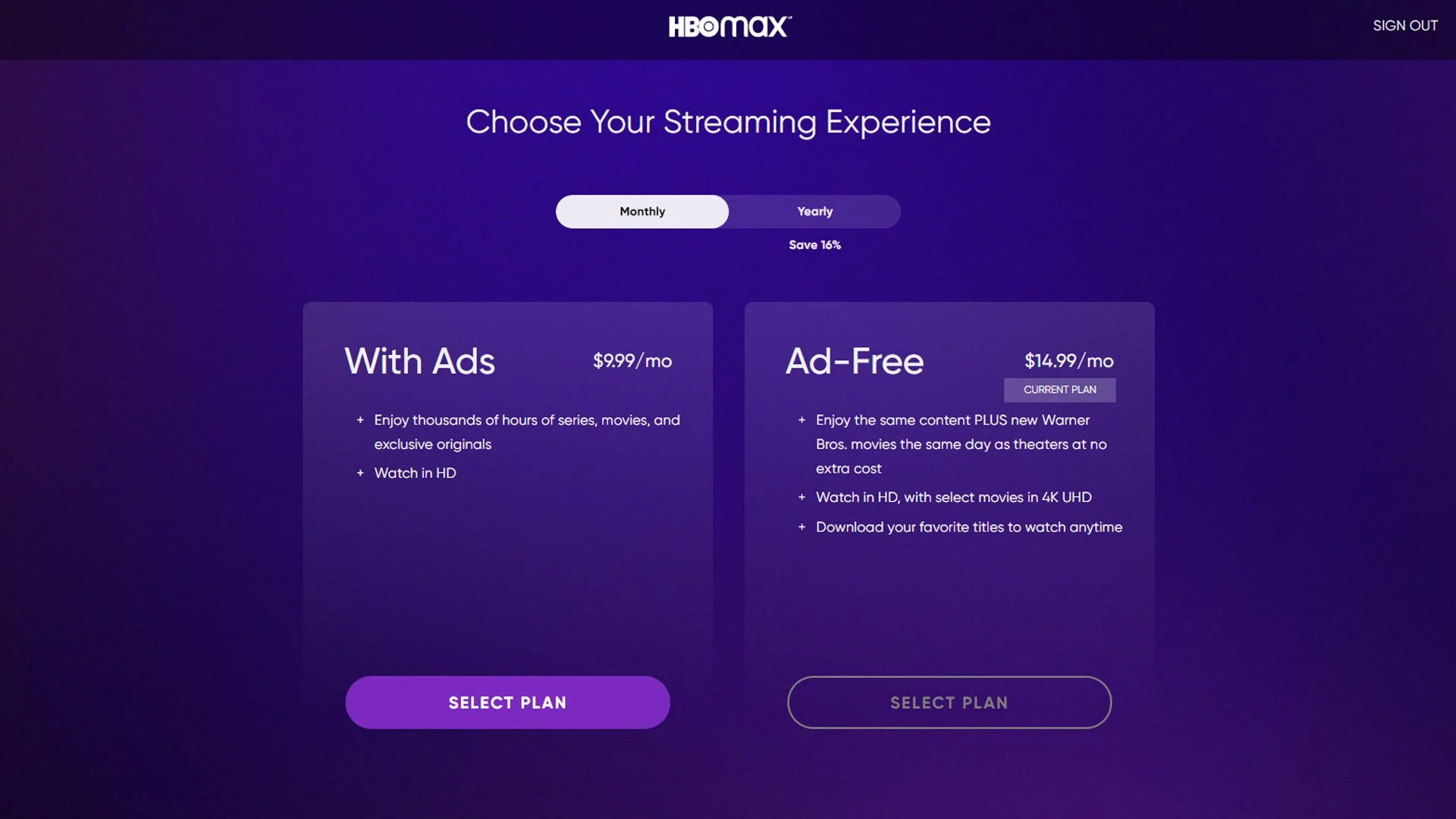

However, the biggest initial hurdle for HBO Max was its price tag of US$14.99 per month which, at the time, was seen as top-tier. Netflix’s standard subscription cost in mid-2020 was US$12.99 (an asking price which had already raised eyebrows over recent increases), while Disney-owned Hulu charged US$11.99 per month for its premium tier without ads.

However, the biggest initial hurdle for HBO Max was its price tag of US$14.99 per month which, at the time, was seen as top-tier. Netflix’s standard subscription cost in mid-2020 was US$12.99 (an asking price which had already raised eyebrows over recent increases), while Disney-owned Hulu charged US$11.99 per month for its premium tier without ads.

Ironically now in 2022 that US$14.99 per month for HBO Max does not seem extraordinary with rivals increasing their prices across the board.

A year and a month after it first launched, HBO Max introduced a US$9.99 per month advertising-supported offering. Promising “the lightest ad load in the streaming industry,” HBO Max’s cheaper tier does not impose advertising on HBO shows like The Sopranos which were initially broadcast without ads, so users could theoretically not see a single advert should they exclusively watch HBO-branded content.

For the quarter ending in June 2021, HBO Max had a total of 47.0 million subscribers. That total stood at 77 million at the end of Q1 2022, when AT&T handed control of WarnerMedia over to Discovery, which has its own streaming ambitions including a merged HBO Max-discovery+ offering.

In the time since adding adverts, AT&T and Warner execs never explicitly told investors or press about the breakdown between fully-paid and ad-supported subscribers. But it is clear to see that a cheaper point of access for HBO Max – combined with increased visibility and compelling content – has benefitted it.

Bailey argues that for streamers like HBO Max, it is not necessarily in attracting subscribers where the addition of advertising helps most. He says: “I think the main benefit for operators is that these hybrid strategies are effective at reducing churn rather than adding subscribers.”

Not for everyone

So while all signs point to advertising-supported options being the future of SVODs there will still be outliers like AMC – and their reasoning also makes sense, says the analyst. “I believe that these companies will be effectively doubling down on the premium nature of their services. It could also be reflective of concerns that existing subscribers would not react well to such changes or even technological concerns around implementation of advertising on their platforms.”

Apple TV+ is an SVOD which shows no indication of ever incorporating advertising (pictured: Severance)

Another platform focused on creating a premium experience that immediately jumps to mind is Apple TV+, which is part of a wider ecosystem of apps and services from the iPhone maker – and none of those services have ads.

Such specialist platforms like The Criterion Channel and Mubi also tend to have a tighter bond with their subscribers who are actively forgoing quantity for a curated experience. As proved by the enduring popularity of Criterion’s filmmaker-approved blu-ray and DVD business, these kinds of subscribers also tend to have a higher level of disposable income and will be willing to pay more if they feel they are getting the desired experience. As such it is unlikely that the addition of advertising to these kinds of services would go far to entice in non-hardcore fans of the service’s subject matter.

Ultimately, it’s clear that there’s no one-size-fits-all model for advertising in streaming. While the addition of ads may benefit the major streaming operators like Disney and Netflix for obvious financial and subscriber number reasons, there are others for whom that rapid expansion is less of a focus.

While advertising-supported options may become the norm rather than the exception in the coming years, there will still be SVODs out there for whom the benefits of advertising do not outweigh the cons.