After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Quibi’s problems stretched beyond a pandemic

After little more than six months on the market, Quibi has announced that it is to shut down.

The news came as a surprise to many in the industry – not that the platform failed to make an impact, but rather the speed in which the streamer managed to crash and burn.

In a letter to investors and users, CEO Meg Whitman and founder Jeffrey Katzenberg attributed the failure to a combination of timing and “because the idea itself wasn’t strong enough to justify a standalone streaming service.” Both of these points are salient, but by no means the only reasons for Quibi’s demise.

Here are the key reasons for why Quibi failed to make the positive impact on the market it aspired to conquer.

Bad branding, legal troubles and PR woes

Quibi was facing an uphill battle the moment that it was announced with that name. Quibi.

As a descriptive portmanteau it is cute and fairly useful at conveying what the service is to people in the know. But as a brand competing for people’s wallets against the likes of Netflix and Disney+ it seems quirky at best and a joke at worst. (Quibi has spent the past few months being the butt of many jokes from John Oliver on Last Week Tonight and has been a perennial whipping boy for the industry.)

But as if being a punching bag wasn’t bad enough, a litany of public-facing missteps and legal troubles ensured anything but a smooth launch.

For starters, it quickly emerged that Quibi had been leaking customer data to third parties without consent – something Quibi said was an error and immediately rectified. Following this, tech firm Eko accused the company of stealing the rotating video technology which was so central to the appeal of the mobile-only Quibi. Quibi won that initial legal battle, but Eko said it will pursue damages even though the streamer is shutting down.

Another controversy saw allegations of nepotism, after it emerged that Reese Witherspoon was reportedly paid US$6 million to narrate a documentary for Quibi. Not that the acclaimed actor is not qualified for the role, rather that her husband had been hired as head of content acquisition and talent not long before Fierce Queens entered production. Quibi denied any suggestion of this, but it was a case where the negative press already had done the damage.

Reports also emerged of tensions between the CEO and the founder, with Whitman apparently articulating complaints of overreach from Katzenberg as early as 2018.

Reports also emerged of tensions between the CEO and the founder, with Whitman apparently articulating complaints of overreach from Katzenberg as early as 2018.

In the weeks following, analysts found poor subscriber projections and a conversion rate of only 8% following the streamer’s free trial.

All of this snowballed towards an inevitable outcome when the Wall Street Journal reported that advertisers like Walmart and PepsiCo were seeking revised terms on their deals. This left Quibi’s shuttering as a matter of when, not if.

As Eric Schiffer, CEO of private equity firm Patriarch Organization says: “It was the scream before the death. Advertisers realised the platform was not performing and Quibi took its first look at its death.

A fundamental lack of audience understanding

Millennials have short attention spans, are always on their phones, are obsessed with celebrities, and love to frivolously spend money on overpriced coffee because they know they’ll never be able to afford a house or to retire.

One must imagine that these were the kinds of thoughts being had by Katzenberg and co. when they were dreaming up the product that would go on to become Quibi: create content with star-power that’s available on-the-go and is quick to watch – and monetised.

While they may have had a vague understanding of what the audience was, there was a fundamental misunderstanding of what they actually want.

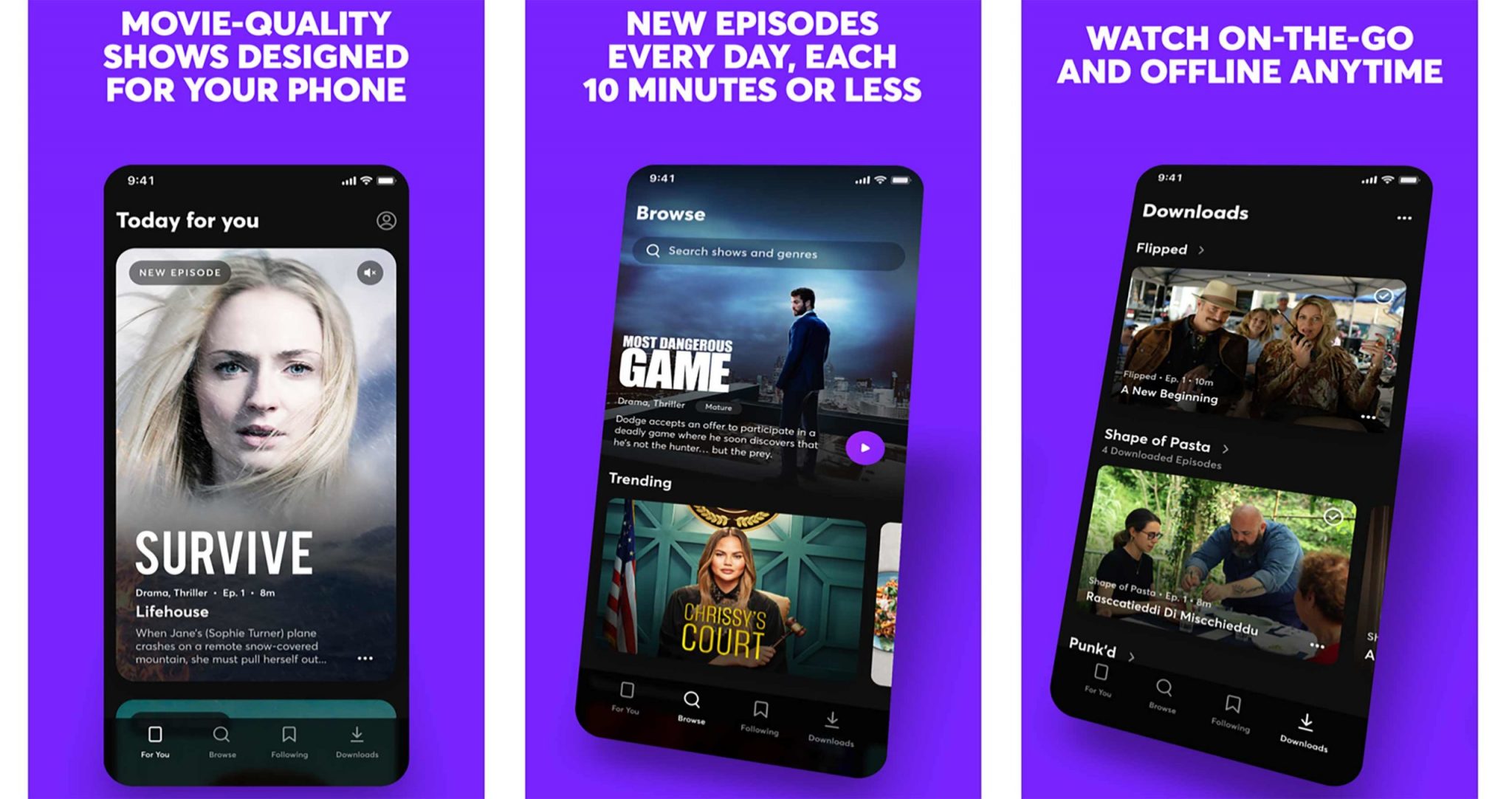

Because while much of the analysis around Quibi’s launch was putting it up against the Netflixes of the world, Quibi was instead competing for time with social media apps and creator-driven platforms like YouTube.

Certainly, the contrasting fates of Quibi and TikTok – the Chinese short-form video app which exploded in popularity in 2020 – could not be more pronounced.

Sarah Henschel, senior research analyst at Omdia explains: “A lot of Quibi’s appeal was short form content with high profile celebrities. However TikTok also has high profile celebrities posting content and it’s entirely free to view.

“The growth of strong short-form AVOD/social media content has taught consumers that they should not have to pay for that kind of content.”

“The growth of strong short-form AVOD/social media content has taught consumers that they should not have to pay for that kind of content.”

The analyst goes on to speculate that Quibi could sell some of its tech – including the patented Turnstyle – to the likes of TikTok, Snapchat or Instagram.

A premium cost, but not a premium service

Users evidently preferred the experience of and were more engaged with those aforementioned social media apps, but Quibi’s biggest blunder was arguably its costing structure.

In a world where its target audience are accustomed to using TikTok et al. for free, not even offering the option of a free, ad-supported tier put up a barrier to entry which immediately turned many off, despite the promise of more premium content. Instead, Quibi started at US$4.99 with ads, rising to US$7.99 without.

Henschel says: “Since the beginning I have felt that Quibi’s price points were much too high for the quantity and value of content offered.”

Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat are all entirely free with ads, while YouTube offers a premium component which removes ads and offers other features like offline viewing. Earlier this year, YouTube said that it had converted 20 million of its 2 billion monthly users into paying customers, but it took years for it to even consider the prospect of launching a paid-for offering.

Schiffer argues that “free is crucial for short form,” but also highlights another mistake made by Quibi in regards to the paid-for elements of its model: “Quibi’s choice to ask for users credit card for a trial was the single worst marketing move of 2020 and pure arrogance that blew up in their face.”

All considered, it is little surprise then that a report from The Diffusion Group said that Quibi would need to launch a free ad-supported tier if it had any chance at success.

This would all be one thing if users were actually engaging with the content, but that did not even seem to be the case.

In June, Douglas Clinton, a former research analyst at Piper Jaffray and current managing partner at Loup Ventures, bluntly said that Quibi lacked compelling content and that it was “losing the attention game.”

In June, Douglas Clinton, a former research analyst at Piper Jaffray and current managing partner at Loup Ventures, bluntly said that Quibi lacked compelling content and that it was “losing the attention game.”

He wrote: “Given the demands on our time, we pay attention to new things that elicit some emotion. Things that bore us elicit no emotion, and we ignore those things. Things that excite us elicit emotion, and we often share those things. Quibi’s content isn’t bad, it’s perfectly fine. It’s just hard to get the attention of a new audience without very compelling content.”

Schiffer surmises that “the content was weak and didn’t stack up against a free to use TikTok nor the quality of huge players like Netflix and Disney+.”

With the names attached, many will surely be interested in watching at least some of Quibi’s content – which is why Katzenberg is confident in recovering some of the cost in sales to broadcasters and OTT operators – but Schiffer does not think this will translate to a significant amount of revenue.

“This was an economic earthquake that decimates the vision of high-dollar celebrity-produced short form entertainment streaming,” the CEO says. “Quibi will sell off its content library at fire sale prices.”

Executive hubris

Schiffer describes Quibi’s billing as “pure arrogance,” but the same could be said for the service as an entire concept.

Quibi was squarely targeted at a millennial audience, but the two faces of the company who were attracting all of the confidence from Hollywood couldn’t have been further removed from that demographic.

I have covered Quibi’s generational divide in regards to its management extensively in a previous piece, but the universal fact remains that regardless of whether or not you are in the bracket you’re designing a product for, you need to be conscious of what the audience actually wants rather than just going on gut instinct alone.

Gone are the days where audiences will put up and shut up when it comes to content on their screens. With an excess of options and abundance of choice, users will not hesitate in switching off if they have no interest in engaging with the product.

An unforeseen pandemic

Trouble was brewing ahead of launch when Quibi had to cancel its April 5 launch event. The pandemic was nowhere near its peak in the US, but the country was recording 30,000 new cases of Covid-19 on a daily basis and, despite a lack of federal guidance on a national level, Americans were already starting to brace for the serious economic and social impact.

Despite an initial couple of weeks in which Quibi was downloaded 2.7 million times, the cracks were starting to show and Katzenberg, on cue, blamed an initial poor performance on the coronavirus.

The combination of Quibi’s cost and a society in which people were not looking for ‘quick bites of content’ on the go, meant that the service was about as far removed from pandemic-friendly as possible

It is far too speculative to ask whether Quibi would have done better in a climate unafflicted by a highly contagious novel coronavirus. It is likely that there would have been less pressure to rush out support for casting to TVs, and less of a chance that it would develop and roll out dedicated CTV apps mere hours before announcing its closure.

But as described above, Quibi had foundational and existential issues that had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Schiffer is very damning, arguing that “Katzenberg’s excuse that they failed because they launched during a pandemic is bogus.”

While Covid may not have been the reason for Quibi’s failure, it certainly did not help, and the unfavourable economic climate it spawned meant that investors demanded immediate results which were not forthcoming.

Henschel describes surprise that there were no serious talks of a sale or absorption into another company, but explains that “since the investor companies need more cash to get through Covid, they are looking to return as much money to them as possible.”

Investor pressure is also a reason why, despite potentially being better for the company in the long-term, the option to delay the launch was not considered.

Quibi had huge stakes, huge risks, and ultimately a huge loss.