After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Netflix dominated the 2010s but can it continue its stratospheric rise in the new decade?

Netflix has finally surpassed its latest milestone of 200 million subscribers, cementing it as the biggest company in streaming – and it’s not even close.

Disney, considered by many as the first major competitor to Netflix on a global scale, sits at a relatively paltry 137 million subscribers globally across its services like Disney+, Hulu and Hotstar. Amazon Prime meanwhile is at 117 million across the globe, though it remains unclear as to how many of those subscribers actually use the Prime Video platform and how many are signed up for the other aspects of the membership like expedited delivery.

As Omdia senior analyst Rob Moyser surmises in the research house’s recently released report Netflix: Strategies for the 2020s: “Netflix is well established as the world’s leading online video service.”

This is a position which has been accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the company admits as much. Speaking on Netflix’s earnings call, CFO Spencer Neumann said that the pandemic had “accelerated that big shift from linear to streaming entertainment” for the entire industry, with the streamer alone adding 37 million paid memberships in 2020.

In terms of revenues, the company made more than US$24 billion for the year – up 24% year-over-year – while operating profit grew by an even larger margin of 76% to US$4.6 billion.

This translates to greater financial stability, with Netflix execs telling shareholders that the company no longer has a need to raise external funding for its day-to-day operations.

The company has dominated the industry for a decade, but, Moyser says, “it is clear that Netflix cannot stand still and expect to thrive.”

Increasing investment from the likes of Disney and Amazon, along with the introduction of heavy hitters such as WarnerMedia, ViacomCBS and NBCUniversal to the SVOD market “threatens to not only stymie Netflix’s future growth but also presents a challenge to its hard- won customer loyalty, as users consider a shift to other VoD players,” Moyser says.

In order to remain at the front of the pack, Netflix will continue to evolve its strategy in the coming years to maintain steady growth and differentiate itself from rivals.

Content focus

As arguably the first major mainstream SVOD, Netflix built up a reputation in its early days as the go-to place to find a large amount of well-known shows and movies from major studios. This by no means has changed, but the calibre of much of the licenced content available on Netflix has diminished in recent years.

Disney first started pulling back its content in 2017, while mainstay comfort TV like Friends and The Office have become core parts of their licence holders’ own streaming services. The Office on Peacock in particular was responsible for 9.2% of all SVOD-streamed content in the first week of 2021, with the show’s launch on the NBCUniversal streamer having a direct correlation with increased sign-ups.

Netflix probably did not imagine the situation getting quite so extreme when it launched its first original series House of Cards in 2013, but the company has since then developed what co-CEO Reed Hastings described as a “virtuous cycle” of original content production.

Nowadays, Netflix is better known for its seemingly bottomless well of bingeable original content that dominates the zeitgeist. Tiger King became an early pandemic memeable phenomenon, while the October release of The Queen’s Gambit was Netflix’s biggest ever limited series with 62 million member households watching it in its first 28 days, and was the source of a revitalised interest in chess.

The company has spent even more money on its 2021 slate, and has upped its focus on movies as cinemas continue to be closed. Last week, Netflix put out a star-studded video trailing its 2021 slate of movies, with more than 70 originals to be released this year and the promise of at least one new film per week. Co-CEO Ted Sarandos however said that “it’s likely more than 70” films with “plenty of room to grow that.”

Omdia’s Moyser outlines the approach: “One of the reasons for this continual investment has been to ensure Netflix was in a strong position to fend off competition from new players like Disney, Warner Media, and NBCUniversal before they had fully entered the market. Its strategy therefore has been to focus on building a tent wide enough to cater to as many consumer tastes and needs as possible, before its competitors gain greater ground on the global stage.”

The increasing focus on content production however is something of a double-edged sword for consumers. A recent price increase in the UK has made the streamer cost more on a monthly basis than a TV licence, and the service is under increasing scrutiny over its upped monthly cost around the world. The report notes that pricing is the most important factor for Netflix users in the UK and France, indicating that this may increasingly become a sticking point in the future for budget-conscious subscribers.

Moyser says that “this uptick in price may harm potential uptake in the next few years as new VoD players such as Disney test various markets with much cheaper entry prices.”

Disney+, which itself will up its prices in February, is embarking on the next phase of its SVOD’s development, with the launch of the new Star hub internationally and a slate of original series tied into the Marvel and Star Wars franchises.

This is another aspect of Netflix’s business that the company will want to improve upon. Shows like Stranger Things and The Crown are major sellers for Netflix, but they are far outweighed by the pull of franchises like the Disney-owned Marvel Cinematic Universe or the Harry Potter films which are owned by NBCU. By comparison, shows like Stranger Things can only go on for a few seasons, while Disney has a years-long roadmap of shows and movies for its properties.

Moyser points out that Netflix has “signalled an interest in developing its own franchises… which have a broad-audience and a PG-level family-friendly feel.”

Though it is not a family-friendly property, The Witcher already has the makings of a tentpole franchise for Netflix, with plans for a spin-off prequel series already in the works. Netflix also purchased comic book company Millarworld in 2017, and has been developing titles with an eye for franchise potential.

While original content will be the focal point going forward, Netflix will continue to acquire content and do major deals such as the acquisition of Studio Ghibli’s global distribution rights and the co-production arrangement with ViacomCBS’s Nickelodeon and Dreamworks Animation (though Moyser says that this partnership “appears more uncertain as rights are sold to other VOD players).

International appeal

The US is becoming a more crowded pool with major telcos and broadcasters all wanting to capitalise on the cord-cutting trend.

As such, Netflix has become “an increasingly global service” and is looking for growth outside of its native country. In 2020, 83% of Netflix’s annual additions came from outside of the US and Canada. EMEA accounted for 41% of Netflix’s full year paid net adds, while APAC added an additional 9.3 million subscribers.

An increasing budget in Europe – Netflix spent US$1 billion in the UK alone in 2020 – is also “a key feature in enticing new subscribers and retaining old ones, with Netflix continuing to set up new production houses in several markets including the UK, France, and Italy,” Moyser says.

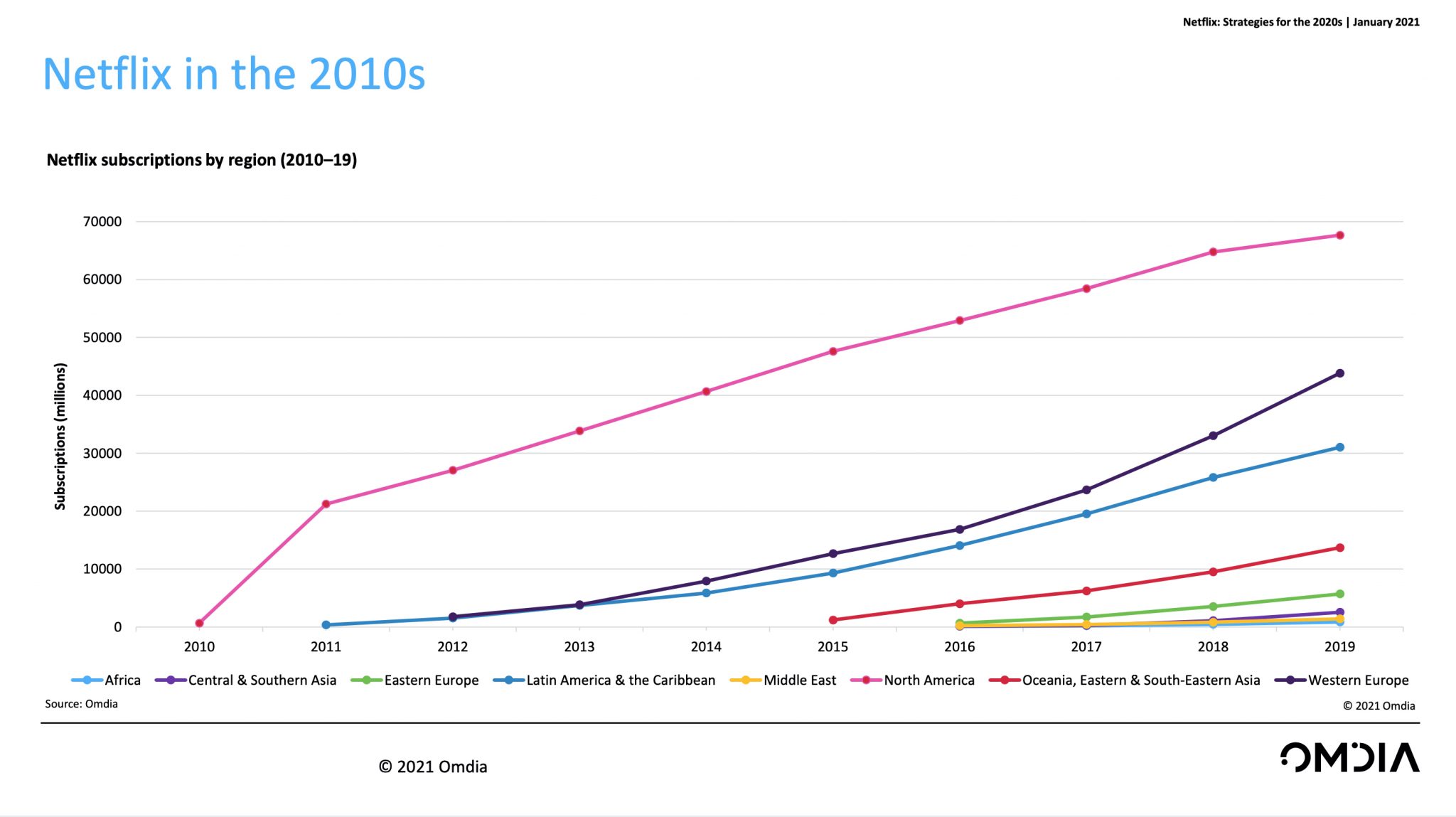

But outside of these mature markets like the US and Western Europe, the chart below shows how the steady gains in the US are being eclipsed by the rate of growth in emerging areas like Africa, Central and Southern Asia, and Southeast Asia.

India is a key area of growth for Netflix. The company has spent US$400 million in the country alone since 2019 on original and licenced content.

Moyser explains the appeal of India and Netflix’s strategy in the country: “This focus on local content in India is of particular importance to the company as it considers localisation and ‘differentiated content’ vital to reaching a broader set of Indian consumers, especially those outside the large cities, while also having the added benefit of appealing to consumers outside India, particularly across Asian and Middle Eastern countries.”

Despite being less of a mature market, competition in Indian SVOD is fierce. Disney is a leader in the market thanks to its acquisition of IPL rights holder Hotstar – with the cricket competition being watched for 383 billion minutes by viewers in 2020 – while Amazon is “the third-largest OTT operator and has invested heavily across the region in recent years,” Moyser says.

Netflix similarly faces competition from local companies like Eros Now which merged with STX Entertainment last year after becoming the first Indian OTT company to get distribution in China the year prior.

Indonesia is also a country that Netflix will want to expand in while also leaning on this base of content built up in India. Another Asian nation dominated by Disney, Netflix has a total of 850,000 subscribers in the world’s fourth most-populated country, which is, like India, one ripe for growth.

Mobile focus and competitive costs

One way that Netflix will continue to grow in Asia is via an increased focus on low-cost mobile-only options.

Moyser says: “To enter markets with poor fixed broadband connections and high mobile penetration, Netflix must build on its early forays into mobile-only plans. Focus on this area can drive major increases in consumer subscription numbers.”

He adds that this approach stands “in stark contrast to its previous entries into new markets.”

“This emphasis was illustrated by its partnership with Indian telco giant Jio in July 2019, which provided customers free subscription to Netflix with Jio’s bundled offers, a deal that in 2020 is set to help Netflix gain an estimated 4.6 million paid subscribers,” he says.

The company is making gains in Asia thanks to this strategy, but Moyser argues: “Netflix’s inroads into Asia will not generate the same level of income as in other regions, with package prices far lower compared to other markets globally. This is despite 2020 being the best year of growth in Asia & Oceania so far, with the region mainly growing in revenue in 2020 after prices rose in Australia.”

This is a strategy also being employed by Amazon, which last week launched a low price mobile-only Prime Video offer in India with Airtel. Amazon has even undercut Netflix, with a monthly cost of INR89 (€1) per month versus Netflix’s INR199 (€2.59) per month.

How will Netflix fare in the 2020s?

2020 was undoubtedly an unprecedented year for all aspects of life and industry. But while many struggled, home entertainment has flourished and Netflix has been a key beneficiary.

The immediate future looks positive, but Netflix is unwilling to look too far ahead.

During its earnings, Netflix warned that 2021 will see more modest growth. It has set a target of 6 million subscriber adds in Q1 2021, while the CFO Neumann said that after that “it’s just so difficult [to predict] in this time” and added that the company would not be providing a full year guide.

“It’s hard enough to project the next 90 days, let alone the next 12 months,” he said.

If it is hard to predict the next 12 months, trying to predict the next decade would be a fool’s errand. But provided that consumer habits continue to trend towards OTT consumption and that Netflix delivers on its promise to ramp up its original productions, there is little more that the company could have done to give itself a better launchpad for the coming years.