After more than 40 years of operation, DTVE is closing its doors and our website will no longer be updated daily. Thank you for all of your support.

Does the licence fee present genuine value for money? Analysing the BBC’s Value for Audiences report

An embattled BBC set out its stall this week in defense of a funding model which has become a target for the UK government.

From the earliest days of his time as prime minister, Boris Johnson has had reform at the broadcaster squarely in his sights. Following comments on the campaign trail that his government is “certainly looking at” abolishing the licence fee altogether, Johnson launched a review into licence fee non-payment decriminalisation – a review which was unceremoniously dumped last month. DCMS committee chair Julian Knight has also called the licence fee a “poll tax regardless” of whether Brits actually “come into contact with the BBC,” while other senior government figures have attacked the funding and editorial directions of the broadcaster.

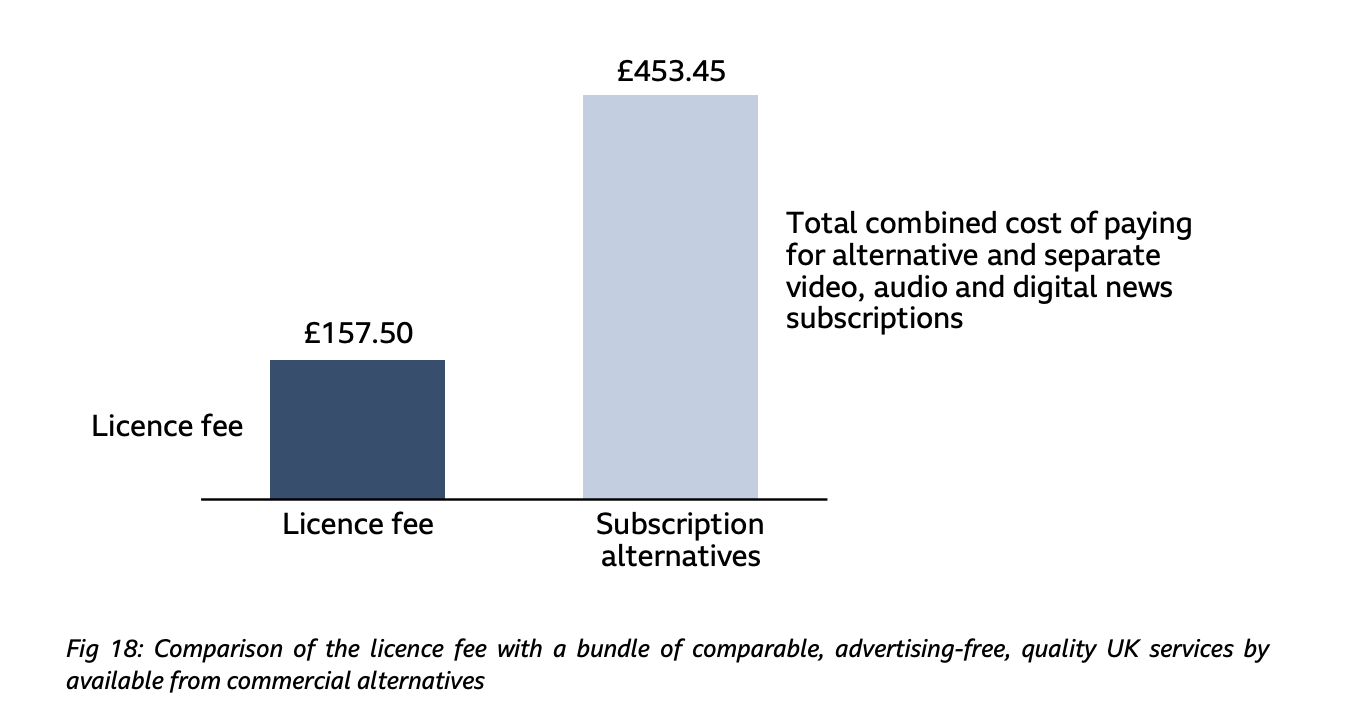

But in its Value for Audiences report, the BBC has put out a clear message: the licence fee is the best way of preserving the public institution, that it presents the most viable financial commitment for users and that an equivalent subscription to cover all BBC services would cost £453.45.

The current financial commitment is an annual fee of £157.50 per household, and the broadcaster claims that this translates to a much better value proposition than other forms of televisual entertainment.

The report says that an hour of watching the BBC costs around 9p on average, compared to 15p per hour for the average SVOD and 50p per hour for a pay TV service. Comparing it to other forms of entertainment ideally accessible in a non-lockdown world, the report says that the licence fee is equivalent to the price of five Premier League match tickets, three London theatre tickets, six zoo visits or 22 cinema tickets.

The report says that an hour of watching the BBC costs around 9p on average, compared to 15p per hour for the average SVOD and 50p per hour for a pay TV service. Comparing it to other forms of entertainment ideally accessible in a non-lockdown world, the report says that the licence fee is equivalent to the price of five Premier League match tickets, three London theatre tickets, six zoo visits or 22 cinema tickets.

The proposed subscription alternative fee is made up of “the average cost of an annual subscription, taken from a small sample of large media providers in the UK who offer subscription video on demand, advertising-free music streaming or digital news subscriptions.”

But more than simply highlighting the benefits of the licence fee, the report aims to show that the BBC is a financially viable institution in its current form thanks to measures that it has been implementing. It does this by claiming to be “a smarter saver,” a “smarter seller”, and a “smarter spender.”

Cutting costs, cutting content, cutting corners?

Measures taken so far include reducing the managerial paybill, cutting overheads, growing commercial income, and increasing the proportion of income spent on content.

All of this, it would posit, has created a media company that is leaner and more efficient. This is highlighted by the BBC’s estimated average annual productivity savings rate of 2.3% compared to the government’s average of under 1%.

But amidst all this is a fear that while the BBC is so focused on cutting costs, its content offering may struggle to compete with that of pay TV providers and international streaming giants. This fear was compounded last month with a report from the National Audit Office (NAO) which said that the BBC’s spending has exceeded its income for three of the past five years.

The BBC is quick to talk about how little an hour of its programming costs to watch, but this is going on the assumption that all TV is created equal – something patently untrue when one considers the astronomical sums spent by the likes of Netflix, Disney, Amazon and others on their streaming exclusive shows.

Spending large sums of money does not necessarily ensure a good show (take the US$40 million per season Netflix shelled out on the critically panned Hemlock Grove for evidence of that), but more than a few eyebrows will be raised by the report’s quiet mention of the fact that the BBC is slashing more than £400 million from its programming and services budget this year.

In-house produced shows like Killing Eve continue to perform well, as do its co-productions with the US like The Serpent and Normal People, but these handful of zeitgeist-grabbing titles pale in comparison to the relentless output of Netflix and now Disney with its Marvel and Star Wars series.

If we are in the so-called ‘golden age’ of television, it would be hard to argue that the BBC has contributed significantly to the canon of prestige TV over the past 20 years.

Likewise, the BBC’s dwindling live sports TV coverage makes it a much less compelling buy for fans of any of the UK’s top leagues, with even the Six Nations likely to go behind a paywall from next year. Last year’s decision from the English Premier League to include the BBC in its project restart plans highlighted just how far away the broadcaster is from being competitive in this space with BT and Sky.

And it is hard to imagine that changing any time soon. While the BBC’s commercial income grew by 50% to £1.6 billion in 2019/20, the NAO report noted that broadcaster received £3.52 billion from the licence fee in 2019/20 – down 8% from 2017/18.

The licence fee is the overwhelming source of operating income for the BBC. Its perceived lack of meaningful content, which has rightly or wrongly turned users away, won’t be improved by people not paying for the licence fee under this current model.

The extreme version of this reading would put the BBC in a death spiral wherein it continues to lose licensees because they don’t see value in the content, and it can’t produce the content demanded because it doesn’t have enough revenue from people paying for the licence fee. Something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The BBC admits that it is in a tough situation at the conclusion of its report, as it notes: “Additional savings through productivity gains are becoming increasingly difficult and scope savings are now the predominant form of savings for the BBC. In order for the BBC to deliver its public service commitments, support the creative industries and continue to invest in high-quality, world-class, distinctive content for UK audiences, it will have to do more with less income to spend on programmes and services.”

The broadcaster however is confident in its plan to increase commercial revenues and explore opportunities presented by technological development, and its institutional legacy will always give it a cultural cachet in the public forum.

Vultures, however, are circling; Richard Sharp, a long-time ally to Boris Johnson and heavy Conservative donor, is the new chair of the BBC while the controversially anti-BBC former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre is to reportedly likely to be installed as the chair of Ofcom. Both may outwardly display support for the BBC, but will not hesitate to pick it apart should any weaknesses arise.

For now, director general Tim Davie believes that the broadcaster is on the right path for the future.

“The BBC has made big changes to ensure we provide outstanding value. We are smarter spenders and savers and more efficient than ever before, but there is more to do,” he said.

“The financial challenges and competition we face continue to evolve and while we have demonstrated we can deliver, I want us to adapt and reform further to safeguard the outstanding programmes and services that our audiences love for the future.”

Time alone will tell if the BBC, under Davie, will successfully adapt in the streaming age.